Nitrous Oxide

Nitrous Oxide Drug of the Month: download

Transcript and Sources

What exactly is it? Where does it come from in nature, how is it turned into useable form? How is it consumed?

And now it’s time for the drug of the month, where we dive into the background, science, history, and current trends surrounding a different drug each month. Last month we talked about cocaine, so for September, we’re taking a very different route and looking at a widely available and loosely regulated drug with many medical, commercial, and yes, even recreational, uses: Nitrous Oxide, sometimes called “Nitrous” for short, though the nickname you’re probably most familiar with is “laughing gas.”

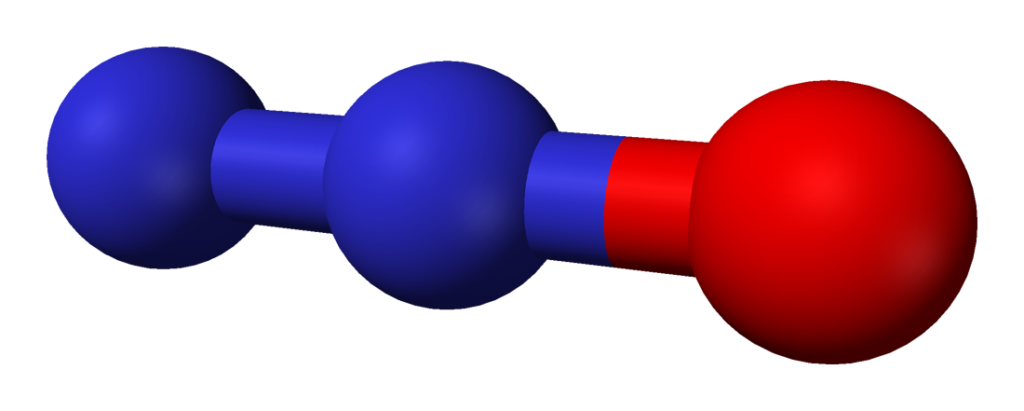

To start off, what exactly is Nitrous Oxide? As you can tell from its name, it’s a combination of nitrogen and oxygen — its chemical name is N2O, meaning the molecule includes two Nitrogen atoms and one Oxygen atom. It’s a gas at room temperature, and it does occur naturally as part of the earth’s nitrogen cycle. This happens through a process called denitrification, where bacteria in the earth’s soil take nitrate (which is NO3, one nitrogen atom and three oxygen atoms) and strip oxygen atoms off of it, creating many byproducts including Nitrous Oxide.

According to the EPA, Nitrous Oxide molecules typically last 114 years before being destroyed by a chemical reaction — the reason the EPA tracks this is because Nitrous is a greenhouse gas, but of course, since this is This Week in Drugs and not This Week in Environmental Science, we’ll be focusing on how it interacts with the human body rather than the planet. And the Nitrous Oxide that is used as a drug is not harvested from soil bacteria, but created in industrial labs.

When producing Nitrous in concentrated form for human consumption or other uses, there are actually a lot of different ways to approach it, but the most common method is by heating up solid Ammonium Nitrate, which decomposes into Nitrous Oxide and water vapour. This was first done commercially in the late 1800s by American Professor George Poe, a notable scientist who was actually the cousin of famous poet Edgar Allen Poe.

Using Poe’s process, after the ammonium nitrate is heated — very carefully heated, I might add, since it can explode if not controlled properly — the hot gas is then cooled to condense the steam, and filtered to remove molecules with more oxygen atoms, and finally put through a triple wash of acids and bases to remove other impurities.

At the end of the commercial process, Nitrous Oxide is highly compressed into liquid form and stored in metal tanks of various sizes. These can range from large tanks as big as a person for uses like doctor’s offices, where they use it as an anesthetic for patients, to tiny cartridges the size of your thumb to be used in small devices for making homemade whipped cream.

These small cartridges, often called “whippits” because of a popular brand name, are the most common way that Nitrous Oxide is consumed recreationally. Grocery stores and other retailers sell small handheld dispensers that are intended to be filled with cream – then, you insert the cartridge into the side, twist it in, which breaks the seal, releasing the gas into the dispenser, which whips the cream as you spray it out the nozzle. If someone wants to inhale pure Nitrous Oxide, they simply don’t put any cream into the dispenser, screw the cartridge in to fill it with gas, and then put their mouth on the nozzle and inhale while squeezing the handle. This makes pure gas come out, rather than whipped cream, which users inhale and slowly exhale. One cartridge is typically used as one dose.

Obviously, this is an off-label use and is not whippet’s intended purpose, but it’s very similar to the way it’s done in a controlled medical setting. In those cases, a mask that covers the mouth or nose is put on the patient, and a precise amount of gas is released from the large tank in order to reach the desired effect of numbing the patient so a procedure can be done with little or no pain. However, these large tanks are also sometimes used recreationally as well, and in those cases people will often fill balloons with the gas before inhaling – this allows it to warm up to room temperature, as the compressed Nitrous Oxide is incredibly cold and could severely harm you if you inhale directly from it. It’s also important to note that with this method, dosage is harder to control since someone could inflate a balloon more or less, rather than a cartridge that is highly standardized.

So, that’s what Nitrous Oxide is and how it’s made and consumed. Next week, I’ll go over how it interacts with the body, its medical and recreational uses, and some of its potential side effects.

What is the science behind how it interacts with the body? What receptors does it influence? What are the medical effects of it, potential side effects?

And now it’s time for the drug of the month, where we dive into the background, science, history, and current trends surrounding a different drug each month. September’s drug is nitrous oxide, and last week we brought you a quick introduction to what exactly Nitrous Oxide is, where it comes from, and how it’s used. Now, it’s time to look at the science of Nitrous: how it interacts with the human body, the effects that make it useful in medicine and recreation, and some of its potential dangers.

As we discussed in last week’s episode, Nitrous Oxide is a colorless gas that’s inhaled by users, typically using a whipped cream canister or a balloon filled up directly from a tank. It’s classified as a dissociative anesthetic, which means it makes users feel a bit detached from both the environment and even themselves. This is very different from a hallucinogen, which alters your senses and can make you perceive things that aren’t there or interpret sensory inputs much differently.

Interestingly for such a widely-used drug, we actually don’t know a lot about Nitrous Oxide’s pharmacological mechanism of action. When inhaled, Nitrous actually doesn’t combine with the hemoglobin in your blood, but travels by itself through your bloodstream and is then excreted, as-is, from your lungs when you exhale. This is a pretty quick process, as the biological half-life of Nitrous is about five minutes, and your body doesn’t convert it into anything – the vast majority of it is in your breath when you exhale.

While we don’t know all of its mechanisms, it has been shown that Nitrous directly modulates things called ligand-gated ion channels, which is a type of protein that opens and closes to allow certain ions, like charged Sodium, Potassium, or Calcium, to pass through a membrane and deliver an electrical signal.

The analgesic, meaning pain-killing, effects of Nitrous Oxide are caused mainly by its interactions with the endogenous opioid system, meaning it acts in a very similar, albeit less pronounced, way to opiates like morphine. Studies have shown that people who build up a tolerance to morphine after taking it over a long period of time also develop a tolerance to Nitrous, so you will feel much less of an effect if you’re taking opiates regularly.

As for Nitrous Oxide’s euphoric effects, that’s due to it releasing dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, a small region at the lower front part of the brain. Unlike most other drugs that cause the release of dopamine, such as cocaine and morphine, there has been some research that shows Nitrous Oxide does not have the same level of reinforcement effects, meaning it doesn’t cause craving to the same extent. This effect seems to vary across species, with mice having no reinforcement, monkeys having some, and humans having more — this means that Nitrous Oxide can become a drug of abuse, but still not to the same extent as drugs like cocaine or morphine.

All of this has led Nitrous to be used as a relatively safe, low-risk anesthetic, which is why it is so common in dentists offices. Since it kills pain while also putting the patient at ease, it’s ideal for things like pulling teeth or other small dental procedures. When used in this setting, doctors will typically attach an apparatus to the patient’s nose, delivering a combination of Nitrous Oxide and oxygen through a hose — this is done to make sure that the brain receives enough oxygen to continue operating, as breathing in only Nitrous can lead to asphyxiation and serious injury. Since the effects are so short-lasting, only about 5 minutes or so, doctors can keep a small amount of the drug flowing, or re-apply it in small doses throughout the procedure. Modern devices also only release gas when the patient inhales, rather than continuously pushing it out, as that would run the risk of filling the room up with Nitrous Oxide and affecting the doctors.

This brings us to some of the risks associated with Nitrous use, as one of the biggest is poor ventilation. Nitrous Oxide, when used responsibly, is quite safe, but there have been some cases of serious injuries because of it. Sometimes people will do stupid things like fill a bag up with Nitrous and put it over their head, or get a large tank and release a huge quantity of it into a room or tent, or even just taking a lot of hits of it in quick succession. This can cause brain damage and other issues, since you need an ample amount of oxygen to survive, and although Nitrous Oxide does include oxygen molecules, they’re not available to your body in the same way that stand-alone oxygen is.

The other most serious risk comes from the method of administration – since Nitrous Oxide in tanks is highly pressurized and incredibly cold, trying to inhale it directly from the tank can burn your skin or even tear your mouth or lungs from the incredible rush of air. Because of this, a good harm reduction strategy is to fill balloons from the tank, in order to let the gas warm up to room temperature before inhaling, which also then lets you control the flow very easily by holding the balloon’s opening.

Taking a standard dose can also cause dizziness, so it’s recommended that the user be sitting down, as taking Nitrous while standing up can cause you to lose your balance and fall. This can actually be one of the most dangerous parts of Nitrous Oxide, as there have been a few documented deaths of people falling a great distance or hitting their head after using the drug.

Nitrous Oxide can be psychologically addictive, so it’s best to use it in moderation. But contrary to popular perception, this is actually quite rare – while Nitrous is sometimes called Hippie Crack, this is due to its short-lasting effects rather than its addictive potential.

While there’s much, much more to it, that’s our overview of the science of Nitrous Oxide. Next week, we’ll go over the drug’s history, and how laws and societal attitudes have changed over time.

- Risks/dangers

- “The major safety hazards of nitrous oxide come from the fact that it is a compressed liquefied gas, an asphyxiation risk, and a dissociative anaesthetic. Exposure to nitrous oxide causes short-term decreases in mental performance, audiovisual ability, and manual dexterity.”

History of the drug. When did people start using it? Who uses it now? How have the laws and societal attitudes about it evolved over time?

And now it’s time for the drug of the month, where we dive into the background, science, history, and current trends surrounding a different drug each month. September’s drug of the month is nitrous oxide, and last week, Sam talked to you about the science behind nitrous oxide, how it interacts with the human body, its medical and recreational uses, and some of its potential side effects. Today, we’ll be taking a closer look at the history of the drug, who discovered and develop its medical uses, when people started using it, and how laws and attitudes around the drug have evolved over time.

As you already know, nitrous oxide is a naturally-occurring gas, produced by bacterial emissions in the Earth’s soil and oceans, and thus also found in the Earth’s atmosphere. It was first “discovered” by an English chemist and natural philosopher named Joseph Priestly in 1772. About twenty years later, an English physician (Thomas Beddoes — like Meadows) and a Scottish engineer (James Watt) got together to develop the first medical, therapeutic uses of nitrous through inhalation and built the apparatus needed to administer it. This paved the way for clinical trials, and Beddoes established a research institute called the “Pneumatic Institution for Relieving Diseases by Medical Air.” Through this institute, a young colleague of Beddoes and Watt’s named Humphry Davy continued experimenting with potential medical uses of the gas, and after witnessing the giggling fits of many of his patients, coined the iconic term “laughing gas.”

Humphry Davy went on to publish a book of his experiments and observations with nitrous, in which he describes inhaling nitrous himself and the pain relief he obtained, hypothesizing that nitrous could be used as an anesthetic in surgical operations. It was another 45 years before doctors actually took note of this gas, and began testing and using it as an anesthetic.

Since the very beginning, nitrous oxide has been preferred by dentists. So 45 years after Humphry Davy’s book, nitrous oxide was used for the first time as an anesthetic drug by American dentist Horace Wells. He had first seen “laughing gas” demonstrations at a traveling circus, and observed that a man who injured his leg while on nitrous, did not feel the pain from his injury until after the effects of the gas wore off, he realized he could use it to similar effect on patients. The very next day, Wells had the carney from the circus who was doing the laughing gas demonstrations come to his office and administer the nitrous oxide to him, and has one of his associates extract a molar. So Wells (the dentist) himself became the first patient to be operated on under anesthesia. Horace Wells never patented his discovery because he believed that pain relief should be ‘as free as the air’.

In the following weeks, Wells treated about a dozen more patients with nitrous oxide to overwhelmingly positive results. But during his first public demonstration, at Harvard Med School, his volunteer patient said he could still feel pain while having his tooth extracted, and Wells was booed off-stage. This led to Wells professional downfall and eventual suicide. It wasn’t until 150 years later that Wells was recognized as the “Discoverer of Anesthesia.”

Ironically, the circus carney who first demonstrated the effects of laughing gas to Wells was a former med student, named Garnder Quincy Colton. Despite Wells’ failure to prove nitrous’s efficacy to the medical establishment, Colton opened up a series of dental clinics all over New Haven and New York City, where he continued using nitrous oxide as an anesthetic, based on Wells’ method. Over the next five years, Colton and his colleagues successfully administered nitrous oxide on more than 75,000 patients, and largely through these efforts, the use of anesthetics in dental surgery eventually became widely accepted.

Meanwhile, as I’ve already alluded to, even during the 18th century, medicine was not the only use for nitrous oxide and was in fact not even the most common use. While nitrous is sometimes referred to as “hippie crack,” recreational use of nitrous did not emerge in the 1970s, but further back to the 1790s. Laughing gas demonstrations like the one where Wells and Colton met had become a fixture of traveling circuses and carnivals, where the public would pay a small price to inhale about a minute’s worth of gas. Posh “laughing gas parties” were also very popular among the British upper class as early as 1799.

As Sam has also previously discussed, the most popular methods for recreational use are either through whippits (the small cartridges meant for whip cream dispensers) or by using balloons filled from larger tanks.

As Sam mentioned in a previous episode, the most common modern-day method for the commercial production of nitrous oxide wasn’t developed until the late 19th-century by an American professor named George Poe, a notable scientist who was actually the cousin of the poet Edgar Allen Poe.

Today, nitrous oxide is used in dentistry as an anxiolytic, which means as an anti-anxiety medicine, in conjunction with a more powerful local anaesthetic. Nitrous is not a very powerful anesthetic, which is why it’s much more commonly used in dental surgery than in more major surgery. Even so, it is usually only administered to the patient as a precursor, to induce euphoria and relaxation, and then while the patient is already under, a more powerful anesthetic is then introduced to inhibit pain.

In the United States, possession of nitrous oxide is legal under federal law and is not subject to DEA oversight. It is, however, regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, which has the authority to prosecute under the Food Drug and Cosmetics Act’s “misbranding” clauses, which prohibits the sale or distribution of nitrous oxide for the purpose of recreational consumption.

Generally, nitrous is available for over-the-counter sales, but many states have laws regulating its possession, sale, and distribution of. Such laws usually ban distribution to minors or limit the amount of nitrous oxide that can be sold without special license. Some states have banned the use of nitrous oxide for recreational intoxication, like California where it’s a misdemeanor.

That’s all for this week’s segment of Drug of the Month and the history of Nitrous Oxide! Next week, Sam will be back for our final Laughing Gas episode with some news and recent trends.

Recent news and trends. Where are things going?

- http://www.sheknows.com/parenting/articles/960623/the-dangers-of-inhaling-nitrous-oxide

- http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/crime/10202484/Laughing-gas-is-party-drug-of-choice-for-young-people.html

- http://www.druginfo.adf.org.au/drug-facts/nitrous-oxide

- http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-23452987

- http://www.globaldrugsurvey.com/the-global-drug-survey-2015-findings/

- http://www.tdpf.org.uk/blog/proposed-ban-nitrous-oxide-political-posturing-wins-out-over-pragmatic-policy

And now it’s time for the drug of the month, where we dive into the background, science, history, and current news and trends surrounding a different drug each month. September’s drug of the month is nitrous oxide, and last week, we learned about its history, who discovered and develop its medical uses, when people started using it, and how laws and attitudes around the drug have evolved over time. Today, we’ll be taking a closer look at the recent news and trends surrounding nitrous oxide.

As I mentioned on last week’s episode, nitrous oxide, also known as laughing gas, has been used recreationally for many centuries. As early as the 1790s, fancy people in the British upper class were holding posh “laughing gas parties.” The trend was revived in the 1960s, particularly in the United States, and particularly by the Grateful Dead, who took to carrying a large tank of compressed nitrous on their tour bus, but it appears to have especially persisted among the UK’s elite. The tabloidy Daily Mail published a piece in 2012 announcing that the celebrity “party drug du jour,” which even Prince Harry had been spotted using, was only now infiltrating middle-class living rooms. By 2015, a prominent British newspaper declared laughing gas [quote] “the party drug of choice for young people.” In the UK, more than 350,000 people between the ages of 16 and 24 reported using the gas in 2012. By 2013-2014, use had risen by more than 100,000 people, up to approximately 470,000 users, according to the UK-based drug policy think tank Transform. Nitrous is now one of the most commonly used drug among young people, nearly twice as popular as cocaine, and second only to cannabis. In the US, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, over 12 million people in the U.S. have tried laughing gas as least once.

In both the UK and the United States, the use of nitrous oxide at outdoor music festivals is becoming increasingly common, where it is often referred to (at least in the media) as “hippie crack.” This nickname is due to its short-lasting effects, which like crack cocaine lasts only a few minutes, rather than its addictive potential, which unlike crack cocaine is very very low. At these festivals, the most popular method of consumption is to fill a regular party balloon with gas from a pressurized tank or canister, and then to inhale the gas from the balloon. This is actually a commonsense harm reduction measure, rather than inhaling directly from the tank, because it allows the nitrous to warm up to room temperature. Compressed nitrous oxide is extremely cold when it comes out of the tank and could severely damage the user’s lips, mouth, and throat if inhaled directly.

Earlier this summer, the UK’s Conservative government passed a law called the “Psychoactive Substances Bill,” which attempts to ban the creation of new psychoactive drugs, and was primarily aimed at curtailing the development of synthetic cannabinoids, such as Spice or K2. However, it is so broadly drafted that it would “make it an offence to produce, supply, offer to supply, possess with intent to supply, import or export psychoactive substances; that is, any substance intended for human consumption that is capable of producing a psychoactive effect.” This circular definition aside, it does contain certain exceptions for [quote] “legitimate substances,” such as food, alcohol, tobacco, nicotine, caffeine, and medical products.

As many drug policy advocates have pointed out, this could actually lead to greater public health risks, without actually reducing use. Instead, it would disincentivize the use of balloons, which as we’ve just discussed, is relatively low-risk, but would obviously be considered an illegal, recreational use, and not a legitimate use. Instead, it would incentivize inhalation through a surgical mask, a misuse of medical devices which can actually creates a much greater risk of asphyxiation.

That’s because the volume of nitrous oxide offered by a balloon is far lower than an anaesthetic dose, and the user is unlikely to lose consciousness; if the rare case that they do, most commonly from holding the gas in their lungs for too long and not breathing enough oxygen, the balloon will simply away fall from the mouth, and they would begin breathing atmospheric air again and recover. With a surgical tube or mask, however, far larger doses can be inhaled, and users will, if they continue to inhale pure nitrous oxide, gradually drift into unconsciousness. If the tube or mask is not then removed at that point, unconsciousness will be succeeded by oxygen starvation and death.

As with alcohol prohibition, and marijuana prohibition, bans on recreational nitrous oxide are unlikely to succeed in eliminating the demand for this substance, and cannot eliminate supply entirely because of all the legitimate medical, commercial, and industrial uses of the gas. So instead, it would just drive the recreational market underground, where the supply is more likely to be contaminated or mixed with other gases, users face greater risks of violence, and all of the other well-known consequences of prohibition will be repeated, which we should all know better by now.

Here in the US, a new trend is emerging in medical uses. While nitrous oxide has long been used in Europe and Canada to ease the pain of childbirth, it has only recently seen a resurgence in the United States. It was once popular for this use in the early 1900s, but was sidelined in the 1930s with the invention of the epidural. But while an epidural can cost up to $3,000, opting for nitrous oxide instead costs as little as $100. The FDA approved new equipment for delivery room use in 2011, which could also help explain the resurgence. According to one report, as few as 5-10 hospitals were using nitrous oxide for women in labor a decade ago. And now several hundred hospitals around the country are giving women that option.

That’s all for this week’s segment of Drug of the Month, recent news and trends in nitrous oxide, and the last episode about nitrous oxide! Next week, we’ll be back with an overview of October’s drug of the month, psilocybin, commonly known as magic mushrooms.

Sources:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitrous_oxide

- https://dancesafe.org/nitrous-oxide/

- https://www.erowid.org/chemicals/nitrous/nitrous.shtml

- http://www.druginfo.adf.org.au/drug-facts/nitrous-oxide