Caffeine

Caffeine Drug of the Month: download

Transcript and Sources

What exactly is it? Where does it come from in nature, how is it turned into useable form? How is it consumed?

It’s now November, and with it comes a new Drug of the Month! We most recently dove into psilocybin, the highly illegal chemical found in magic mushrooms, so this month we’re bringing it back to the world of legal drugs. Our new drug of the month is not only legal, but is actually the most widely consumed psychoactive drug on the planet, with a large majority of adults and even many children consuming it regularly. You guessed it: for November, our drug of the month is Caffeine.

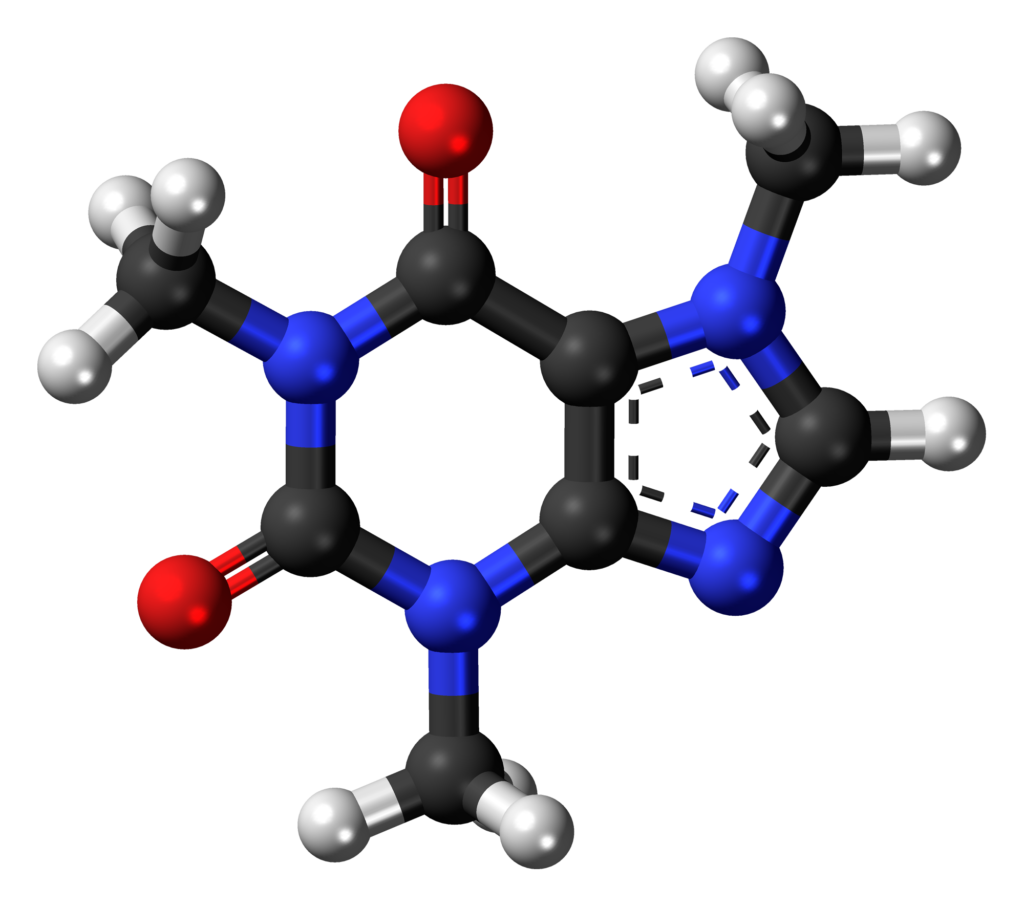

You’ve obviously heard of, and most likely consumed caffeine, but what exactly is it? Pure caffeine is a bitter, white crystalline powder with the chemical structure C8H10N4O2, making it an alkaloid like nicotine and cocaine. It is classified as a central nervous system stimulant but is pretty mild in its naturally occurring forms, which, combined with its long and deeply rooted use by most cultures, has led it to be very loosely regulated in most places, if regulated at all.

One of the main reasons caffeine is so commonly used is because of how plentiful it is in nature. Caffeine is produced by over 60 different plants, including Guaraná, also known as Brazilian cocoa, which is a shrub whose seeds have the highest concentration of caffeine of any known plant. Yerba Mate, native to South America, contains caffeine in its sticks and leaves which are brewed as a tea simply referred to as Mate. Tea plants have a significant amount of caffeine in their leaves, which are brewed into a wide assortment of teas depending on the variety. The Kola tree, native to the tropical rainforests of Africa, has caffeine in its fruit which are known as kola nuts — and you guessed it, kola nuts are used as flavoring in drinks like Coke, Pepsi, and other colas. Cacao, used to make chocolate, also contains caffeine, but in smaller concentrations than these other plants; you’d have to eat between five and ten Hershey chocolate bars to get the same amount of caffeine as a cup of coffee. And, of course, that brings us to coffee, whose seeds (wrongly referred to as coffee “beans” because they look like beans) are the most widely consumed source of caffeine on the planet — every second, people around the world drink over 26 THOUSAND cups of coffee, and in fact, I’ve got a cup on my desk as I’m recording this podcast.

What I find really interesting is that caffeine actually came about in many of these plants through the process of convergent evolution, meaning they took different evolutionary paths to get to it — just last year, a group of researchers who sequenced the coffee genome realized that it used a different enzyme to produce caffeine than the cacao plant. That these two different plants arrived at, then prioritized the production of, caffeine shows that it’s a very biologically useful substance — but what exactly are these plants all using it for?

Now, this is another place where caffeine is pretty unique. It actually seems to have two purposes, which at first seem like they’re working against each other. On the one hand, caffeine can be toxic to insect at high levels, so plants use it to keep bugs from munching on their leaves. Also, when coffee leaves die and fall off, they get caffeine into the soil and make it harder for other plants to grow. But on the other hand, when present in small enough doses, caffeine can actually entice insects. The coffee plant’s nectar contains a small amount of the drug, so pollinators who feed on it will get a little buzz, giving them energy to spread the pollen further, and increasing the likelihood that they’ll come back later for another taste.

But for humans looking to get their own caffeine buzz, how are all these plant sources turned into a useable form? While there are some alternative methods, most caffeinated drinks are prepared simply by brewing the plant’s seeds or leaves in hot water, then draining out the plant matter to leave a caffeinated beverage that can be served hot or cooled down – though there are a lot of variations on this basic concept. For tea, users typically place the leaves into a mesh strainer or buy it in pre-made tea bags, which are then placed in hot water inside a small ceramic cup, left in for a few minutes, and removed. But when consuming Yerba Mate, the teacup is replaced with a specialized hollow gourd, and users actually just place the leaves directly into the hot water, later drinking the Mate through a metal straw with a strainer on the end of it called a Bombilla. And of course, when it comes to coffee, there seem to be infinite ways to brew it: drip, pour-offer, cold-brew, french presses, and more. The more common a drug is, the more variation there tends to be in how it’s consumed, maybe because there’s just more people experimenting, or because of some urge to have your own unique preference within the huge crowd of coffee-drinkers.

But those are all just if you want to prepare caffeinated drinks. What if you just want pure, unadulterated caffeine? We obtain that through a process called decaffeination, which as you can probably tell, removes the caffeine from the plant – but not entirely, meaning decaf coffee does still have some caffeine (around 10 milligrams per decaf cup, compared to about 85 milligrams in a standard cup). There are a few different methods for decaffeination, but two of the most common are water extraction, where the beans are soaked and the water is passed through a charcoal filter that grabs the caffeine out, and supercritical carbon dioxide extraction, where CO2 is put under incredibly high pressure which allows it to penetrate into the beans and dissolve over 90% of the caffeine. No matter the process, you’re left with a bunch of less-caffeinated plant matter, and a bunch of caffeine, which can then be added to other products or taken in its pure form.

While the vast majority caffeine is consumed in beverages, there are also many concentrated caffeine products on the market, such as tablets. You can even buy a bulk bags of pure caffeine powder online, with one teaspoon containing as much caffeine as 25 cups of coffee. This powder can be mixed into other drinks, taken orally by itself, or even snorted.

Though this is rare, it just illustrates how much diversity there is within a drug as popular as caffeine. We’d never be able to fully cover the wide variety of forms it can take, but I hope this overview was a good glimpse into the wonderful world of caffeination. Next week, we’ll be diving into the science of caffeine: how it interacts with your body, its positive effects, and some of the dangers that come along with it.

What is the science behind how it interacts with the body? What receptors does it influence? What are the medical effects of it, potential side effects?

Now it’s time for our drug of the month, where we dive into the details around a different drug each month of the year. For November, we’re looking at caffeine, and since it’s our second installment, we’re focusing on the science of this wildly popular drug, how it interacts with the body, and some of its positive and negative effects.

As stated in the introduction, caffeine is a mild stimulant that is actually the most widely used psychoactive drug on the planet. It’s usually consumed in beverages such as coffee and tea, but can also be present in food like chocolate, or it can even be taken in pill form or snorted as a powder. But no matter the route of administration, caffeine affects your body in the same way.

There are a lot of mechanisms that caffeine uses to produce its characteristic effects, but the most prominent is working as an agonist for adenosine. You see, adenosine is a neuromodulator that slowly increases in your body throughout the day. It causes drowsiness, so once it reaches a certain concentration, it will make you start falling asleep. Caffeine blocks adenosine from acting on its receptor, which delays the feelings of drowsiness that come with it, but since it’s not actually destroying the adenosine, once the caffeine leaves your body, all that adenosine is then left in your system to bind with its receptors and send you to sleep.

Caffeine also stimulates certain parts of your autonomic nervous system, and is able to cross the blood-brain barrier.

Once ingested, caffeine typically takes about an hour for its full effects to be felt by the user. It lasts for about 3 to 4 hours, and is then excreted in your urine. It has a biological half-life of 3 to 7 hours, meaning during that time, half of it will have left your system. Therefore, the more you take, the longer it will take to leave your body.

And the doseage of caffeine can vary widely, both between products and between users. As a general rule, a cup of coffee has about 80 to 100 milligrams of caffeine, a cup of tea has about 50mg, and a can of soda has about 30mg. But there is actually a lot of variation within each of these categories. For example, a 16oz coffee from Dunkin Donuts contains 140mg of caffeine, while the same size coffee at Einstein Brothers Bagels has 200mg. And if you think that’s a lot, wait til you look at Starbucks, where a 16oz coffee contains a whopping 330mg of caffeine – more than triple what’s considered a standard cup. So while a coffee from Dunkin may be cheaper, a Starbucks coffee includes 2 1/3 times as much caffeine, meaning it’s probably a better deal if you’re just looking at coffee as a caffeine delivery system (I won’t comment on the taste of each of them since that’s a pretty contentious topic in Massachusetts).

There is also a lot of variation within non-coffee products. Dark chocolate actually contains one to two times the amount of caffeine as coffee by weight, with 80-160mg per 100 grams of chocolate. Caffeine pills usually come in 100mg and 200mg doses, and things like caffeinated gum will usually have 50 to 100mg. Pure caffeine powder is ridiculously potent, and a single teaspoon can contain as much caffeine as 25 cups of coffee, making it very important to measure doses accurately. This has led to some problems with overdoses, which we will be getting to in more detail in installment #4.

And while 85% of Americans use caffeine each day, there’s also a lot of variation in how much users prefer to consume. Generally, older people tend to consume more caffeine per day, with consumption averaging 83mg for 13-17 year olds, 137mg for 25-34 year olds, and maxing out at 225mg for 50-64 year olds. This may be a way to cope with the fatigue that comes with old age, but could also be a result of taste and habit – perhaps even addiction – leading to more consumption of coffee or other caffeine sources.

This brings us to the actual effects of caffeine, which most listeners are probably familiar with through their own lived experiences. The effects that are sought after by caffeine users include increased alertness and improved memory, making it really the only widely accepted, unregulated performance-enhancing drug. Some also use it as an appetite suppressant. Then there are also some beneficial effects that aren’t typically the focus of users, such as lowering your risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. It is also associated with decreased risk for developing cancer, but does carry an increased risk for some specific cancers, such as colorectal and bladder cancer. It may also reduce the risk of nervous system disorders like Parkinson’s and dementia.

The potential side effects of caffeine are also well-known: taking too close to bedtime can lead to insomnia, and taking too much can cause shakiness and anxiety, and long-term use can lead to higher blood pressure. There is currently some debate as to whether caffeine intake during pregnancy carries any risks, but for the time being, caffeine is considered a “pregnancy category C” drug, which is defined as follows: “Risk not ruled out: Animal reproduction studies have shown an adverse effect on the fetus and there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in humans, but potential benefits may warrant use of the drug in pregnant women despite potential risks.”

Yet in extreme cases, caffeine can lead to overdose, sometimes even fatal ones. The LD-50, at which half of people would die of an overdose, is estimated to be between 150-200mg per kilogram od body mass, which means a 70 kilogram adult ( 154 pounds for my fellow Americans) would need at least 10,500mg — over 10 grams, which is more than 31 Starbucks coffees. But due to the high concentrations of caffeine in tablets or powder form, these routes of administration make lethal overdose more possible and there have been a few reported cases of deaths from too much caffeine intake, often in minors or smaller adults.

In contrast to these incredibly rare cases of overdose, the other major risk with caffeine use is dependence. As a stimulant that many people take frequently, caffeine causes a tolerance to build quickly, making users consume more to get the same effects. Since caffeine use is so accepted in our society, caffeine is probably the one addiction that often gets joked about and taken lightly, and you’ll often see coffee cups making light of their owner’s caffeine dependency. Not that this is necessarily a bad thing, but imagine if we had novelty beer mugs joking about alcoholism or novelty syringes with puns about heroin addiction. Obviously, caffeine dependency does not cause the same level of disruption in one’s life as other addictions, but it’s worth considering whether that’s because of the drug itself or our attitudes surrounding it.

And the medical profession is starting to get a bit more concerned about the potential side effects of caffeine. In 2013, the bible of American psychiatry, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-5 for short, added “caffeine withdrawal” as a mental health disorder, signaling that doctors will be paying more attention to it in the future and opening up the ability of health insurers to file claims for it. While there is not a risk of death from withdrawal like there is with alcohol, caffeine withdrawal comes with symptoms like headache, fatigue, anxiety, irritability, difficulty concentrating, and depression. So if you’re a caffeine user like me, it’s best to stay mindful of your intake, and if you find yourself drinking too much coffee, try alternating with decaf or taking a tolerance break for a week or two.

So that’s all for the science of caffeine, installment #2 in November’s drug of the month. Tune in next time for a history of the drug: when humans first discovered it, and how the laws and societal attitudes about it have evolved over time.

When did people start using it? Who uses it now? How have the laws and societal attitudes about it evolved over time?

Now it’s time for our drug of the month, where we dive into the details around a different drug each month of the year. As our long-time listeners remember, in November we covered caffeine but only made it halfway through, giving an introduction and looking at the science before we went on our half-hiatus between seasons. So even though it’s January, since it’s the start of season 2 we’re going to be finishing up our look at caffeine. For this, our third installment, we’re diving into the history of the drug: when people first discovered it, how it became popular, and how the laws and societal attitudes about it have changed over time.

Since caffeine is steeped – no pun intended – in so much history, I’ll barely be able to scratch the surface of it in this five minute segment, but will be giving a quick overview about the origins and histories of some of the most popular sources of caffeine in human culture.

As you may recall from our introduction, caffeine is actually found in over 70 different plants such as coffee, guarana, and kola. Since very little processing is needed, human use of caffeine goes back thousands of years. For example, there’s a rich mythology surrounding guarana, which is native to the Amazon basin. According to a myth attributed to the Sateré-Maué tribe in modern Paraguay, guarana’s domestication originated with a deity killing a beloved village child. To console the villagers, another, nicer god plucked the left eye from the child and planted it in the forest, resulting in the wild variety of guarana. The god then plucked the right eye from the child and planted it in the village, giving rise to domesticated guarana. The origin of this myth probably comes from the visual similarity of guarana beans to eyeballs, since they have a small black spot on a mostly white sphere.

And while many now think of tea as a quintessentially British drink, it’s actually relatively new to the country, and even that region of the world. Like guarana, the origin of tea is also an ancient legend, albeit a much more secular one. So the story goes, in 2737 BC, the Chinese emperor Shen Nung had a servant who was boiling some water to drink by itself, when some leaves from a nearby tree were blown by the wind and fell into the pot. Since he was interested in herbs, the emperor decided to try the infused water and really liked it, going down in history as the first person to drink tea. While certainly more believable than the story of guarana coming from a sacrificed child’s eyeball, it’s impossibly to verify whether this was true, especially since emperors and other dictators have a tendency to take credit for anything they can.

Whether or not Emperor Shen Nung was the first tea drinker, the drink was definitely popular in ancient China. Containers for tea have been found in tombs from the Han dynasty, which went from 206 BC to 220 AD, and it really took off in popularity during the Tang dynasty, which went from 618 to 906 AD. It then spread to Japan, where it became an integral part of their culture as well. It didn’t reach Great Britain until the 1600s, when it was one of many products imported by the British East India Company. It started off as a curiosity, but when some members of the British royalty took a fancy to it, it became popular among the royal court, which then filtered out to the wealthy elites and eventually the rest of the population. Its use became so widespread that when the British government imposed high taxes on its importation, a huge black market was created where people smuggled tea into the islands. Eventually, officials realized the high taxes were causing more problems than they solved, and lowered them to more reasonable levels.

Coffee, the only form of caffeine that can give tea a run for its money in global popularity, also has a rich history stretching far back in human history. It originated in Ethiopia, and the story goes that a goat herder named Kaldi saw his goats filled with energy after eating berries off of a certain plant. He tried them himself and also got a boost of energy, so he informed some local monks who brewed it into a drink and spread it throughout their networks. It was soon moved across the Red Sea to Yemen, where it became incredibly popular and was deliberately cultivated for the first time. To this day, one of the two main types of coffee is known as Arabica, for its agricultural roots on the Arabian peninsula.

As it spread throughout the Middle East, coffee did face some serious opposition. It was banned in Mecca in 1511, and was similarly prohibited in the Ottoman empire beginning in 1623. Some muslim leaders condemned coffee, lumping it in with alcohol, which was already prohibited by the religion, but this did not turn into a religion-wide ban. Despite all of these efforts to stem the popularity of coffee, it continued to expand, eventually reaching Europe. Once it arrived in Italy, some Catholic priests also pushed for its prohibition, asking the Pope to forbid church members from using it. But the story goes that when Pope Clement VIII tried it in order to determine whether to ban it, he loved it so much he not only rejected the request, but joked that it should be baptized. Due to the influence of the church at the time, this surely helped speed up the adoption of coffee by Europeans.

Once coffee had established itself in Europe, it was spread to the Americas during colonization, where plantations thrived in the hot wet climates in central and south America and were operated mostly through slave labor. In colonial America, tea was still more popular than coffee just like it was in Europe, but during the American revolution coffee took the lead since revolutionaries demonized tea as a British drink and promoted the drinking of coffee as an act of patriotism.

Today, there is still some debate as to whether tea or coffee is more popular worldwide. Because of its roots in China, the most populous country in the world, and Great Britain then spreading it throughout its far-flung empire including India, tea is preferred by a much larger number of people. Coffee remains more popular in the United States, most of the Americas, and in continental Europe, which despite their smaller populations, consume a lot more caffeine per capita, helping close the global gap with tea. And as a more objective measure, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, in 2011 there were 8.5 million metric tons of coffee produced globally, compared to only 4.7 million metric tons of tea. But since it takes less tea than coffee to make a single cup, there remains some room for debate as to which is more popular. But whether tea or coffee dominates, one thing is for sure: caffeine is the most widely consumed psychoactive drug on the planet.

Recent news and trends. Where are things going?

And now it’s time for the Drug of the Month, where we dive into the details about a different drug each month. This week, we’re finishing up our focus on caffeine with our fourth installment on some recent trends surrounding the most popular psychoactive drug on the planet.

Caffeine has been a part of human culture for millenia, coming from a variety of sources like coffee, tea, guarana, kola, and over 70 other plants. Though it was used casually since prehistory, the first boom in caffeine’s popularity occurred during the 16 and 1700s which coincided with the Industrial Revolution, with many historians crediting artificial light and caffeine as two major factors allowing humans to function in this new era where work was based around time on a clock, rather than the rising and setting of the sun that set the limits on when farmers could work. We seem to be in the midst of a new spike of caffeine usage over the past few decades, which seems to coincide well with the modern era where people are expected to work long hours at service counters or in front of computer screens, both of which can be easier when under the influence of caffeine.

According to the Food and Drug Administration, 90 percent of people worldwide use caffeine in some form, and there are some global trends in the types of caffeine used throughout the world. As I said last week, tea is more popular in China, the UK, and former British colonies, while coffee is more popular in continental Europe and the Americas. But method of ingestion aside, there are also some stark differences in the quantities of caffeine consumed in different countries. According to the BBC, Finland takes the crown for the country with the highest caffeine consumption, with the average adult downing 400 mg each day, which is roughly equivalent to 4 or 5 cups of coffee – more than double the amount consumed by the average American.

Finland is then followed by Norway, Iceland, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, Belgium, and Canada. Noticing a trend here? Along with sharing some common culture, these countries all share a similarly frigid environment, with some of them far north enough that daylight is incredibly short for certain parts of the year. So it’s likely that these countries’ inhabitants are using caffeine to stay more alert when it’s dark out, and possibly using coffee or other hot caffeinated drinks to stay warm as well.

In the US, there have been some big changes in caffeine intake in recent years. The magazine Pediatrics released a study on the type of caffeine ingested by young people, and from 2000 to 2010, 74% of people under 22 consumed at least some caffeine. In that same time period, soda went from comprising 62% of youth caffeine intake to only 38%, while coffee jumped from 10% to 24%. So young Americans are drinking less soda but much more coffee, which could possibly be due to health and diet concerns, but could also just be a cultural phenomenon with the rise of Starbucks and other trendy coffeeshops becoming the new hangout and status symbol for teens and young adults.

While traditional products like coffee are rising in popularity, there have also been a lot of new caffeinated items coming to market in recent years. Wrigley’s launched a line of caffeinated gum in 2013, called Alert, with each stick containing 40 milligrams of the drug. However, shortly after its debut, the company halted production of the gum after the FDA voiced concerns, and it has not yet returned to store shelves.

Another product that took the nation by storm, becoming wildly popular but then crashing nearly as fast, was alcoholic energy drinks loaded with caffeine and other stimulants. Four Loko was the most talked-about brand, but there was a large variety of other products with names such as Joose and Max. I remember seeing these all over the place in 2010, as they were very popular with college students who were looking to party late into the night, and pushing things to the edge to test their own limits or impress people around them. But after a few high-profile accidents and a massive drug scare in the media, the FDA issued warning letters to the four biggest manufacturers in November of 2010, saying that the administration viewed the products as not being “generally recognized as safe,” which is the legal standard. Several states even went so far as to ban these beverages, which combined with the FDA warning, led Four Loko and others to reformulate their products, removing caffeine and no longer marketing it as an energy drink.

However, these crackdowns on certain highly caffeinated product hasn’t stopped other companies from putting caffeine in all sorts of things. There’s STEEM caffeinated peanut butter, Perky Jerky, which is exactly what it sounds like, energy gummy bears, BANG caffeinated ice cream, Jelly Belly extreme sports jelly beans, and there’s even an Indiegogo campaign going on right now for a new line of caffeinated toothpaste. As of this recording, it’s raised over $15,000 towards its $42,500 goal.

But the caffeine product that’s gotten the most attention in the past year was barely a product at all, but merely pure caffeine powder. Many companies began marketing this online, with a five-pound bag running as little as 10 or 15 dollars. Pure caffeine powder is ridiculously potent, and a single teaspoon can contain as much caffeine as 25 cups of coffee, making it very important to measure doses accurately. This potency has led to the deaths of at least two people who did not measure carefully enough, or intentionally consumed large amounts without understanding the potency and risk. Due to these accidents, major retailers such as Amazon.com have stopped selling pure caffeine powder. Some are calling for a complete ban, but at this point, it’s still legal and possible to get on specialty websites. The FDA has taken a more cautious approach with caffeine powder than it did with Four Loko, simply issuing a consumer advisory in December 2015 to educate people on the facts and risks associated with these products.

While it seems like completely pure caffeine powder is the most extreme form of intake possible, who knows what sort of trends we’ll see in the future. So that wraps up the fourth and final installment of caffeine as our Drug of the Month! Since next week is the 5th Sunday in January, we’ll have a special segment for our listeners, and will then be returning with a brand new Drug of the Month in February.

Sources: