Ritalin

Ritalin Drug of the Month: download

Transcript and Sources

Introduction

And now it’s time for the Drug of the Month, where we talk about the background, science, history, and recent news and trends in a different drug each month. We’ve been on hiatus for the past two months, but we’re back this week with a back-to-school special for September’s Drug of the Month – Ritalin. At first, we wanted to examine the culture and phenomenon behind study drugs more generally, but given how chemically different the different medications are, we decided to focus on just Ritalin for this month, since it’s the oldest, and examine different types of amphetamines, such as Adderall, later on down the road. But because Ritalin, and especially Adderall, are often prescribed and used interchangeably, I’m going to do a little bit of a side-by-side comparison for our Introduction episode only.

Ritalin is the trade name for methylphenidate, which is a central nervous system stimulant that’s primarily used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). It is, however, also medically approved for narcolepsy. The original patent was owned by CIBA, now Novartis Corporation. It was first licensed by the FDA in 1955 for treating what was then known as “hyperactivity,” particularly in “maladjusted children.” Adderall was licensed much more recently, in 1996. Both Adderall and Ritalin are commonly prescribed psychostimulants that produce effects such as increasing or maintaining alertness, combating fatigue, and improving attention.[13]

Medical use began in 1960; but prescription of the drug has become increasingly popular since the 1990s, when the diagnosis of ADHD became more widely accepted.[4][5] Between 2007 and 2012 methylphenidate prescriptions increased by 50% in the United Kingdom and in 2013 global methylphenidate consumption increased to 2.4 billion doses, a 66% increase from the year before. This number is still dwarfed by prescriptions of Adderall, which was approximately 1.6 million for patients 10-19 years old in the United States in 2011, versus just 260,000 prescriptions in the same demographic for Ritalin. That’s about six times as many Adderall scripts as Ritalin.

The United States continues to account for more than 80% of global consumption.[6][7]

ADHD and other similar conditions are believed to be linked to sub-performance of the dopamine and norepinephrine functions in the brain, primarily in the prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive functions, like, reasoning, inhibition control, organization, problem solving, planning, etc.[8][9]

Methylphenidate’s mechanism of action involves reuptake inhibition of certain neurotransmitters, primarily as a dopamine reuptake inhibitor. It acts by blocking the dopamine and norepinephrine transporters, leading to increased extracellular concentrations of dopamine and norepinephrine. This effect in turn leads to increased neurotransmission of dopamine and norepinephrine. In contrast, and this is the super simple version, but Adderall functions by BOTH increasing levels AND ALSO inhibiting reuptake of those neurotransmitters. Sam will explain all of this more in depth during next week’s Science episode.

In the United States, methylphenidate is a Schedule II controlled substance, which means it has known medical benefits, but also a high risk of abuse. Adderall is also found in Schedule II. Methylphenidate may also be prescribed for off-label use in treatment-resistant cases of bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder.[18] Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of magnetic resonance imaging (MRIs) suggest that long-term treatment with ADHD stimulants (specifically, amphetamine and methylphenidate) actually decreases abnormalities in brain structure and brain function found in subjects with ADHD.[19][20][21] Moreover, reviews of clinical stimulant research have established the safety and effectiveness of the long-term use of ADHD stimulants for individuals with ADHD.[22][23] The addition of behavioural modification therapy (such as cognitive behavioral therapy) can have additional benefits on treatment outcome.[27][28]

Current models of ADHD suggest that it’s associated with functional impairments in some of the brain’s neurotransmitter systems,[note 1] particularly those involving dopamine and norepinephrine.[30] Psychostimulants like methylphenidate and amphetamine may be effective in treating ADHD because they increase neurotransmitter activity in these systems.[30] Approximately 70% of those who use these stimulants see improvements in ADHD symptoms.[31][32] Children with ADHD who use stimulant medications generally have better relationships with peers and family members,[22][31] generally perform better in school, are less distractible and impulsive, and have longer attention spans.[22][31] An 8-week study with 25 children diagnosed with ADHD compared the efficacy of Ritalin, Adderall, and a placebo. Results demonstrated that both drugs were significantly better than a placebo for behavioral improvements, academic productivity, and staff/parent ratings of behavior.

Researchers noted that Adderall produced a greater improvement than Ritalin on most measures, and also required a lower dosage overall.

Methylphenidate has been the subject of controversy in relation to its use in the treatment of ADHD. The prescription of Ritalin to children has been the subject of malpractice lawsuits, particularly the issue of misdiagnosis and coercive treatment by school systems. The contention that methylphenidate acts as a gateway drug, however, has been discredited by multiple studies,[153] according to which abuse is statistically very low and “stimulant therapy in childhood does not increase the risk for subsequent drug and alcohol abuse disorders later in life”. People with untreated ADHD are predisposed to having an increased risk of substance use disorders, and stimulant medications actually reduce this risk.[33][34]

Methylphenidate and other ADHD stimulants also improve task saliency and increase arousal.[43][44] Stimulants such as amphetamine and methylphenidate can improve performance on difficult and boring tasks,[43][44] and are used by some students as a study and test-taking aid.[45] Based upon studies of self-reported illicit stimulant use, the primary reason students use stimulants are for its performance-enhancing effects, like as a study aid, rather than for recreational or party use, due to the stimulants’ sometimes euphoric effects. For people who do use Ritalin or Adderall recreationally, the most common method is by crushing tablets into a powder and snorting it.

So that’s all for the introduction to September’s Drug of the Month, where we learned about Ritalin, what it is, what it does, and why people use it. Next week, Sam will be back to chat about the science of heroin, how it interacts with the human body, and some of its potential side effects.

Science

Now it’s time for our drug of the month, where we dive into the details around a different drug each month of the year. For September, we’re looking at Methylphenidate, most commonly known under the trade name Ritalin, and since it’s our second installment, we’re focusing on the science of this widely prescribed drug, how it interacts with the body, and some of its positive and negative effects.

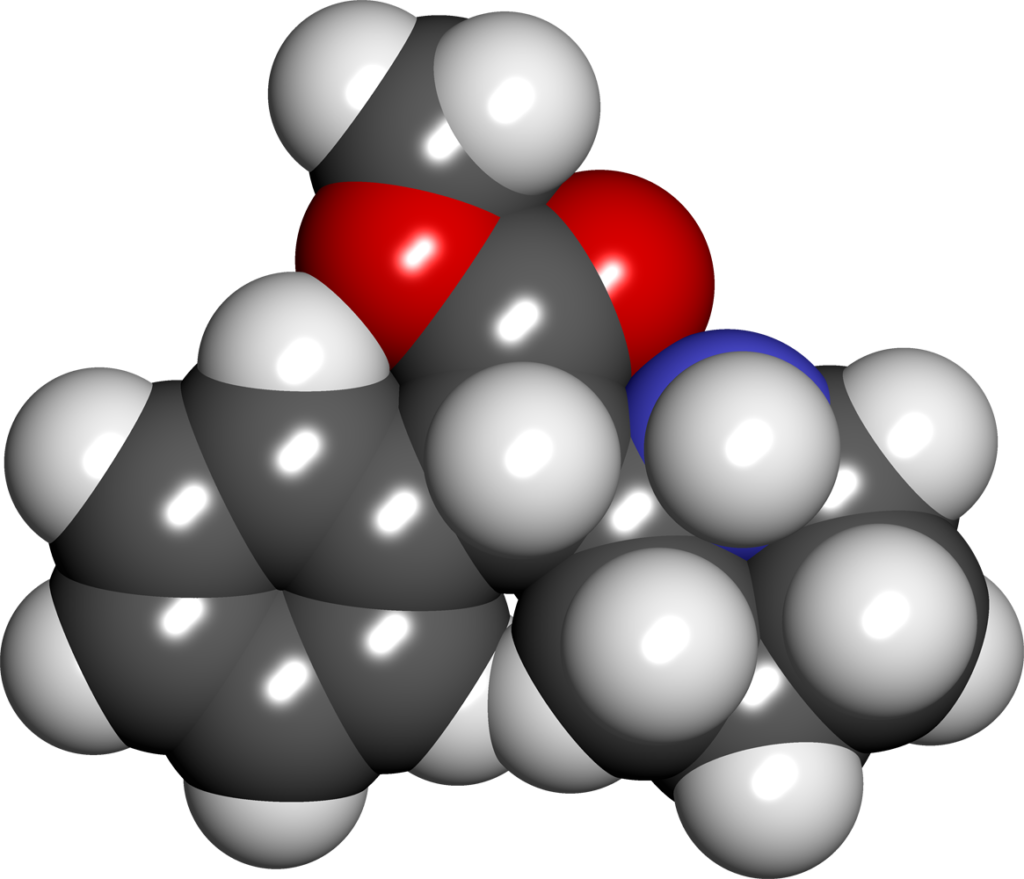

As Rachelle explained in our introduction, Methylphenidate is a central nervous system stimulant that’s used in the treatment of ADHD and narcolepsy, though its use in ADHD is both much better known and more controversial. It is also sometimes prescribed for off-label use in very specific cases of bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder, though being off-label, these are quite uncommon. The chemical formula is C14H19NO2, and it’s considered part of the phenethylamine and piperidine classes. Its first and still most common trade name is Ritalin, though it’s also sold under many different brand names with slightly different formulations.

For example, one of the other well-known brands of Methylphenidate is Concerta, which, in contrast to Ritalin, comes in an extended-release form. Rather than just a single tablet, it has sections that release at various times, with about 22% being released immediately and the remaining 78% then spread over 10-12 hours, compared to Ritalin only lasting about 3 hours. Concerta comes in pills ranging from 18 to 54 milligrams, and is preferred by people who want to take one pill and have it last all day rather than have to keep re-dosing. This is particularly useful for children with ADHD, as their parents can give them their medication before they go to school and not have to worry about them keeping track of their medicine independently.

In addition to the various brands and time-release formats of Methylphenidate, it can also be given through means of administration other than tablets and capsules. Methylphenidate is now also available in transdermal patches and a liquid syrup; though those are less common, it does seem to be geared towards the pediatric market since giving children cough syrup or putting a patch on them for the day can be easier to manage than forcing them to take a pill. The epitome of this focus on children came last year when the FDA approved a Pfizer product called QuilliChew, which is Methylphenidate Hydrochloride in chewable gummy form. This led to some controversy from people who think that ADHD medications are overprescribed, and led to some worries about them encouraging abuse.

However it gets into your body, Methylphenidate works by acting as a norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI), though it’s more effective at regulating dopamine than norepinephrine. This means that it blocks your neurons from re-absorbing these neurotransmitters, leading to greater concentrations of them outside of your cells. When taken orally, Methylphenidate has a bioavailability of about 30%, ranging from 11 to 52% depending on the individual; and it lasts 2-4 hours, unless it’s an extended release. It’s metabolized by your liver, and then mostly excreted out through your urine.

While it’s still in your body, this increase in dopamine and norepinephrine is responsible for its stimulating effects. Because ADHD is believed to be caused by lower-than-average performance of the brain’s dopamine and norepinephrine, stimulating these two neurotransmitters is basically intended to bring those levels up to the average baseline so that people with ADHD can then function normally. However, like most drugs, they don’t work for everyone, though about 70% of people who try Methylphenidate for ADHD report noticing improvements in their symptoms. For the treatment of narcolepsy, it works basically the same way – for those unfamiliar, narcolepsy is a sleep disorder where people get incredibly tired and fall asleep without warning, so using a stimulant like Methylphenidate can increase alertness and stave off those random bouts of exhaustion.

Of course, it’s this same mechanism of action that makes the drug so appealing to people without ADHD or narcolepsy, who, rather than getting their dopamine and norepinephrine up to normal levels, can use Methylphenidate to make them increase to far above normal. The off-label use of Methylphenidate as a study drug or other productivity aid is well-known, particularly among college students in demanding programs, or who just don’t want to study that much and would prefer some kind of shortcut. The culture and debate over the ethics of performance-enhancing drugs in academia is something we’ll get into in the episodes on Methylphenidate’s history and current events. But on the science side, studies have found that these anecdotal reports of performance enhancement are born out, with numerous clinical trials finding modest yet clear improvements in cognition and memory in normal healthy adults. These improvements are most noticeable when working on otherwise boring or repetitive tasks, which make it so useful for rote memorization but can also lead to problems – talk to enough people who use Methylphenidate as a productivity enhancer, and you’re sure to hear some stories of someone setting out to study for an exam and then spending hours cleaning their house instead.

In addition to the fairness concerns over Methylphenidate, there are concerns about off-label use leading to medical problems, and it is true that Methylphenidate comes with side effects. A mild to moderate overdose leads to nervous system overstimulation, which then leads to a wide variety of issues including vomiting, agitation, tremors, muscle twitching, confusion, hallucinations, delirium, hyperthermia, sweating, headache, tachycardia, and heart palpitations. In extreme overdoses, it can even lead to paranoia, convulsions, and even put you into a coma. So, whether people are taking Methylphenidate with a prescription or without, they should be very careful to monitor their dosage, as mistaking extended release capsules with standard capsules could be incredibly dangerous.

Because it can induce euphoria, just an academic way of saying that it makes you feel good, Methylphenidate also has the potential to become habit-forming. This is very uncommon in therapeutic doses, since the drug is not too bioavailable and is released relatively slowly, but if you, say, open up a capsule and snort the powder, or take much more than the normal dose, these can lead to higher concentrations in your body and increased feelings of euphoria. But, as we’ve explained in many other episodes, addiction is a complicated thing that also has a lot to do with your physical and social environment, so causing euphoria will not by itself get you addicted to Methylphenidate. But, if you’re lonely or otherwise lacking happiness in your life, it’s more likely you will become addicted to a drug that gives you that feeling, however short-lived.

That’s all for the science of Methylphenidate, more commonly known under the brand name, Ritalin. Next week Rachelle will be back with the history of this drug – how it was first created, and how our legal and societal attitudes about Methylphenidate have evolved over time.

History of the drug

And now it’s time for the Drug of the Month, where we take a closer look at a different drug each month. For September, we’ve been learning more methylphenidate, better known by its brand name Ritalin, and last week, Sam talked about the science behind Ritalin and how it interacts with the human body. On today’s episode, I’ll be discussing the history of Ritalin, the origins of its use, and evolving societal attitudes towards Ritalin users.

Methylphenidate was first synthesized in 1944, and was identified as a stimulant in 1954. As I mentioned in this month’s Intro episode, the original patent for Ritalin was owned by CIBA, now Novartis Corporation, and was first licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1955 for treating what was then known as hyperactivity. Methylphenidate was synthesized by Ciba chemist Leandro Panizzon. His wife, Marguerite, had low blood pressure and would take the drug as a stimulant before playing tennis. Allegedly, he named the substance Ritalin, after his wife’s nickname, Rita.

In 1957, Ciba Pharmaceutical Company began marketing Ritalin to treat chronic fatigue, depression, psychosis associated with depression, narcolepsy, and to offset the sedating effects of other medications. It was also used into the 1960s to attempt to counteract the symptoms of barbiturate overdose. For a short time, methylphenidate was sold in combination with other substances as lifestyle products, particularly in a tonic of hormones and vitamins, marketed as Ritonic in 1960, intended to improve general mood and maintain vitality.

Research on the therapeutic value of Ritalin began in the 1950s, and by the 1960s, interest focused on the treatment of “hyperkinetic syndrome” or “hyperactivity,” which would eventually be called Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (or ADHD). In the United States, the use of Ritalin and other stimulants to treat ADHD steadily increased in the 1970s and early 80s, but between 1991 and 1999, Ritalin sales in the United States sky-rocketed 500 percent. In the 1990s, the US accounted for 90% of global use of stimulants such as methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine. By the early 2000s, this had fallen to 80% primarily due to increased usage in other countries. In 2003, doctors in the UK were prescribing about a 10th of the amount per capita as that prescribed in the US, while France and Italy accounted for approximately one twentieth of US consumption. According to a 2015 report by the International Narcotics Control Board, the United States continues to account for more than 80% of global consumption of methylphenidate.

Beginning in the 1980s, a series of lawsuits were filed based on the perceived harmful side effects of Ritalin. In the late 90’s, with the significant increase in prescription of Ritalin, a minor but vocal group of critics began raising the alarm that a crisis was on hand. A series of five federal lawsuits filed in five separate US states in 2000, known as the Ritalin class-action lawsuits, alleged that the manufacturers of Ritalin and the American Psychiatric Association had conspired to invent and promote the disorder ADHD in order to create a highly profitable market for the drug. By the end of 2002, just two years later, all five lawsuits were dismissed as frivolous or otherwise withdrawn.

According to an article by the Los Angeles Times, “the uproar over Ritalin was triggered almost single-handedly by the Scientology movement.” The Citizens Commission on Human Rights, an anti-psychiatry group formed by Scientologists in 1969, were behind a major campaign against Ritalin in the 1980s and lobbied Congress for an investigation into Ritalin. Scientology publications themselves admitted that the “real target of the campaign” was “the psychiatric profession itself.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attention_deficit_hyperactivity_disorder_controversies

Indeed, controversy surrounding the use and over-prescription of Ritalin is intimately tied to the perceived over-diagnosis of ADHD or even the validity of ADHD as a mental disorder.

For example, the British Psychological Society wrote in a 1997 report that physicians and psychiatrists should not follow the American example of applying medical labels to such a wide variety of attention-related disorders: [Quote] “The idea that children who don’t attend or who don’t sit still in school have a mental disorder is not entertained by most British clinicians.” [End Quote]

Compounding this skepticism is the fact that the pathophysiology of ADHD is unclear and there are a number of competing theories as to its origins. Frequently observed differences in the brain between ADHD and non-ADHD patients have been discovered from various types of neuroimaging, but it is uncertain if or how these differences give rise to the symptoms of ADHD. Although ADHD is said to be highly heritable and twin studies suggest genetics are a factor in about 75% of ADHD cases, it has also been argued that ADHD is a heterogeneous disorder[8] caused by a complex interaction of genetic and environmental factors and thus cannot be modeled accurately using the single gene theory. Authors of a review of ADHD etiology in 2004 noted: “Although several genome-wide searches have identified chromosomal regions that are predicted to contain genes that contribute to ADHD susceptibility, to date no single gene with a major contribution to ADHD has been identified.” Regardless, it has been argued that even if ADHD is a social construct, this does not mean it is not a valid condition. For example, obesity is often the result of various environmental factors, in addition to a genetic predisposition, yet it still has demonstrable adverse health effects associated with it.

It has also been argued that over-diagnosis occurs more frequently in higher-income communities, whereas under-diagnosis occurs more frequently in under-privileged and minority communities due to lack of resources and lack of financial access. Those without health insurance are statistically less likely to be diagnosed with ADHD.

Over-diagnosis is also far more likely in young, male patients, whereas female patients are more likely to be under-diagnosed. The ratio for male-to-female patients is 4:1 with 92% of girls receiving a primarily inattentive subtype diagnosis, rather than hyperactive. This difference in gender can be explained, for the most part, by the different ways boys and girls express symptoms of this particular disorder. Typically, girls with ADHD exhibit less disruptive behaviors and more internalizing behaviors. Girls tend to show fewer behavioral problems, less aggressive behaviors, less impulsivity, and less hyperactivity than boys diagnosed with ADHD. These patterns of behavior are less likely to disrupt the classroom or home setting, therefore allowing parents and teachers to easily overlook or neglect the presence of a potential problem. This leaves many women and girls with ADHD neglected. Studies have shown that girls with ADHD, especially those with signs of impulsivity, were 3-4 times more likely to attempt suicide when compared with female controls. Additionally, these girls were 2-3 times more likely to engage in self-harming behaviors.

Currently, ADHD management recommendations vary by country and usually involves some combination of counseling, lifestyle changes, and medications.[28] The British guideline only recommends medications as a first-line treatment in children who have severe symptoms, and otherwise recommends medication only for those who either refuse or fail to improve with counseling.[29] Canadian and American guidelines recommend that medications and behavioral therapy be used together as a first-line therapy, except in preschool-aged children.

In the end, mountains of clinical research have established the safety and effectiveness of long-term stimulant use in the treatment of ADHD. Indeed, magnetic resonance imaging studies (MRIs) suggest that long-term treatment with amphetamine or methylphenidate actually decreases physical abnormalities in brain structure and function.

That’s all for this week’s segment of Drug of the Month. Next week, Sam will be back with current news, trends, and events surrounding Ritalin.

Trends

Now it’s time for the fourth and final installment of September’s Drug of the Month. This month, we’ve been looking at methylphenidate, more commonly known under the brand name Ritalin, starting off with an intro, the science, and history of the drug. Today, I’ll be wrapping up our focus on methylphenidate by addressing some current trends and news in the usage and discussion around Ritalin.

As Rachelle explained last week in our history segment, methylphenidate was first synthesized in 1944, and first licensed by the FDA in 1955. It began as a drug with a relatively small patient population, but its use steadily grew and has exploded in recent decades. Now, 60 years after it was first approved as a medicine, about 4% of American adults say they have used methylphenidate at some point in their lives, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. This has coincided with the growth of ADHD diagnoses, which account for the vast majority of prescriptions in comparison to methylphenidate’s use for treating narcolepsy. The drug accounts for about 23% of ADHD prescriptions in the United States, less than Adderall, which has 38%, but more than Vyvanse, which only has 16%.

While methylphenidate is prescribed to both children and adults, much more attention and controversy has followed the huge growth in prescriptions to youth in the United States. About six million children, which is 15% of the country’s kids, are now diagnosed with ADHD. Among boys, that number jumps up to 20%. This has attracted much attention, and while nearly everyone agrees that the diagnosis and medication is correct and helpful for many children, there is a range of opinion on how many actually need to be treated with pharmaceuticals, with some defending the current diagnosis rate and others saying it should only be about 5%, not 15.

Just this month, a new book on the subject came out, entitled “ADHD Nation: Children, Doctors, Big Pharma, and the Making of an American Epidemic.” It chronicles the origins of the drugs, controversies in its marketing and research, and includes many interviews with people involved in making methylphenidate as popular as it is today.

With our massive pharmaceutical industry and the large numbers of people diagnosed with ADHD, this surge in global methylphenidate production and consumption has been driven largely by the United States. But other countries have started to go in the same direction, with prescriptions for methylphenidate and other ADHD drugs doubling over the past decade in the United Kingdom, totaling nearly a million prescriptions in a country with only 64 million people. This is less than in the United States, but perhaps surprisingly, the US is not the #1 prescriber — that distinction goes to Iceland, at least when you’re doing it on a per capita basis. In Iceland, there are 15 daily doses of methylphenidate per 1,000 inhabitants, nearly double the 8 doses per 1,000 Americans.

Partly driven by, and partly driving, this surge in methylphenidate prescriptions is a growing variety of methods to consume the drug. Originally marketed in a capsule, methylphenidate is now available in a wide variety of forms, including a chewable formulation called QuilliChew that was approved by the FDA in December 2015. This, of course, fed into the controversy around its use, with supporters seeing it as a convenient way to deliver medicine to children, and critics seeing it as a way to make over-medication easier and more enjoyable.

Aside from the ongoing controversy over ADHD in children, methylphenidate was also in the national discussion earlier this month, when Russian hackers stole medical records from the World Anti-Doping Association (WADA) and published them online. These included the records of multiple Olympic athletes, such as American gymnast Simone Biles, whose records showed she had tested positive for methylphenidate. After this got out there, she came out as having ADHD, saying she’d been taking methylphenidate since she was a child, a fact confirmed by the WADA. She then struck back against people who criticized her, saying “Having ADHD, and taking medicine for it is nothing to be ashamed of, nothing that I’m afraid to let people know.”

And that’s all for the our look into the recent trends and current events around methylphenidate, also known as Ritalin. We’ll be back next week with a brand new drug to talk about for the month of October.